-40%

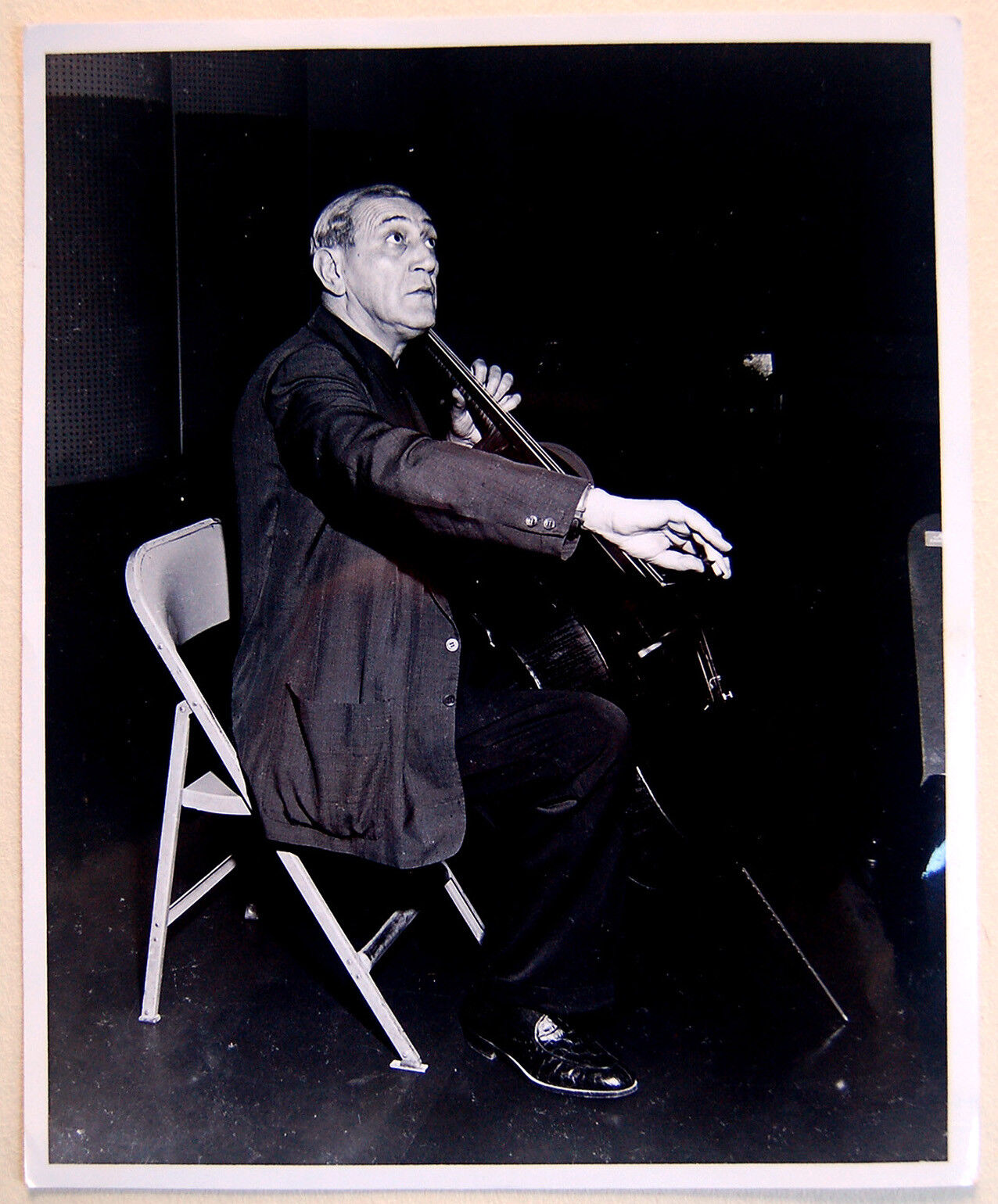

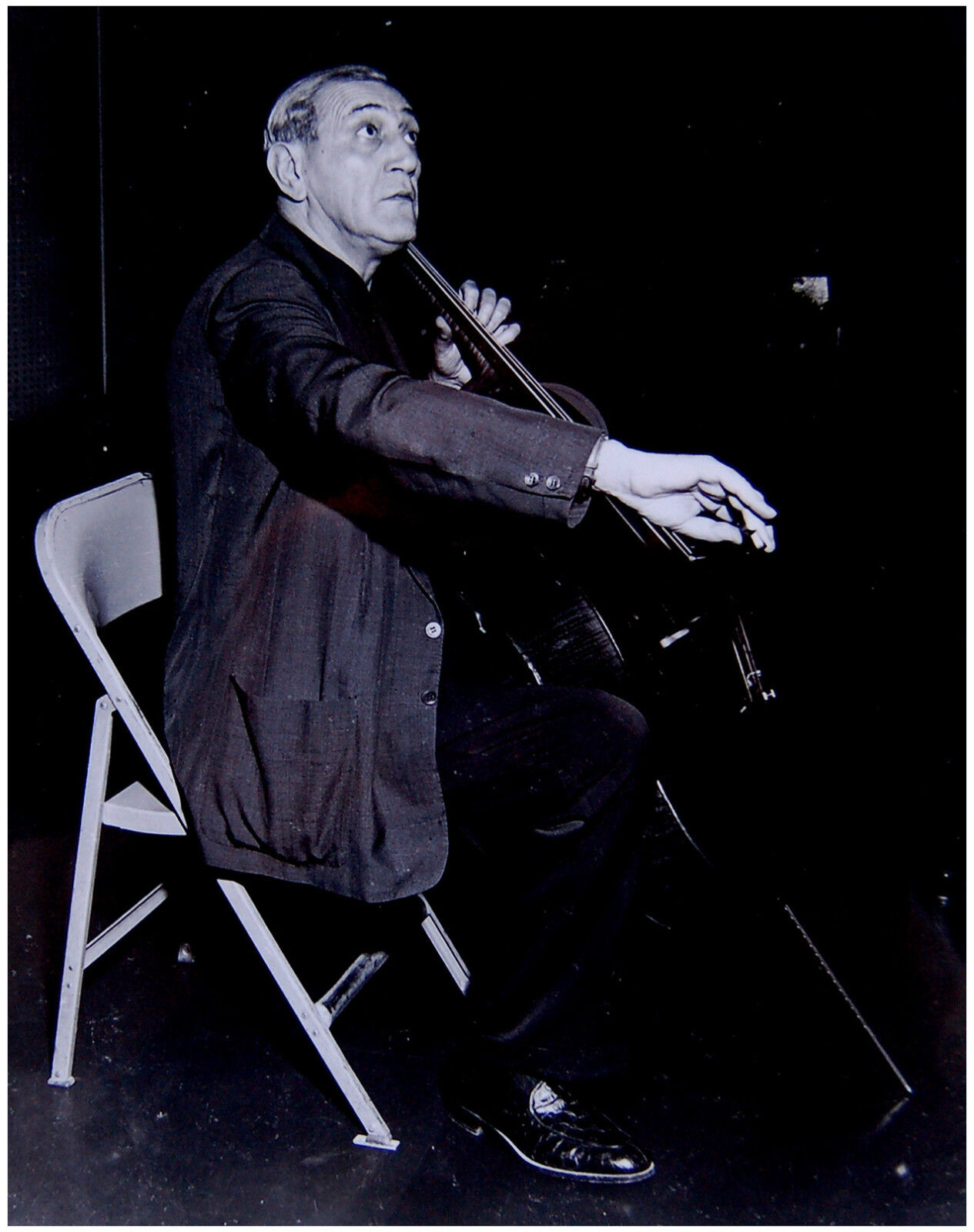

1950 RUSSIAN Cellist GREGOR PIATIGORSKY Original ACTION PHOTO Cello MUSIC Jewish

$ 44.88

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

DESCRIPTION:

Here for sale is an original ca 1950's original ACTION PHOTOGRAPH which was taken during a REHEARSAL of the renowned JEWISH CELLIST of Russian origin GREGOR PIATIGORSKY . The CELLO - VIOLONCELLO rehearsal took place in ca 1950's

. Issued by RCA-RECORDS ( Stamped on verso ) .

It's an ORIGINAL ( Not a reprint !! ) silver gelatine ca 1950's ACTION PHOTO.

Around

8

x 10 " .Excellent condition . Clean. ( Pls look at scan for accurate AS IS images ) Will be sent inside a protective rigid packaging .

PAYMENTS

:

Payment method accepted : Paypal

& All credit cards

.

SHIPPMENT

:SHIPP worldwide via registered airmail is $ 25 . Will be sent inside a protective packaging

.

Handling around 5-10 days after payment.

Gregor Piatigorsky (Russian: Григо́рий Па́влович Пятиго́рский, Grigoriy Pavlovich Pyatigorskiy; April 17 [O.S. April 4] 1903 – August 6, 1976) was a Russian-born American cellist. Biography Early life Gregor Piatigorsky was born in Ekaterinoslav (now Dnipropetrovsk in Ukraine) into a Jewish family. As a child, he was taught violln and piano by his father. After seeing and hearing the cello, he determined to become a cellist and was given his first cello when he was seven. He won a scholarship to the Moscow Conservatory, studying with Alfred von Glehn, Anatoliy Brandukov, and a certain Gubariov. At the same time he was earning money for his family by playing in local cafés. He was 13 when the Russian Revolution took place. Shortly afterwards he started playing in the Lenin Quartet. At 15, he was hired as the principal cellist for the Bolshoi Theater. The Soviet authorities, specifically Anatoly Lunacharsky, would not allow him to travel abroad to further his studies, so he smuggled himself and his cello into Poland on a cattle train with a group of artists. One of the women was a heavy-set soprano who, when the border guards started shooting at them, grabbed Piatigorsky and his cello. The cello did not survive intact, but it was the only casualty. Now 18, he studied briefly in Berlin and Leipzig, with Hugo Becker and Julius Klengel, playing in a trio in a Russian café to earn money for food. Among the patrons of the café were Emanuel Feuermann and Wilhelm Furtwängler. Furtwängler heard him and hired him as the principal cellist of the Berlin Philharmonic. United States In 1929, he first visited the United States, playing with the Philadelphia Orchestra under Leopold Stokowski and the New York Philharmonic under Willem Mengelberg. In Ann Arbor, Michigan, in January 1937 he married Jacqueline de Rothschild, daughter of Édouard Alphonse James de Rothschild of the wealthy Rothschild banking family of France. That fall, after returning to France, they had their first child, Jephta. Following the Nazi occupation in World War II, the family fled the country back to the States and settled in Elizabethtown, New York, in the Adirondack Mountains. Their son, Joram, was born in Elizabethtown in 1940. From 1941 to 1949, he was head of the cello department at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, and he also taught at Tanglewood, Boston University, and the University of Southern California, where he remained until his death. The USC established the Piatigorsky Chair of Violoncello in 1974 to honor Piatigorsky. Piatigorsky participated in a chamber group with Arthur Rubinstein (piano), William Primrose (viola) and Jascha Heifetz (violin). Referred to in some circles as the "Million Dollar Trio", Rubinstein, Heifetz, and Piatigorsky made several recordings for RCA. He played chamber music privately with Heifetz, Vladimir Horowitz, Leonard Pennario, and Nathan MilsteinPiatigorsky also performed at Carnegie Hall with Horowitz and Milstein in the 1930s In 1965 his popular autobiography Cellist was published. Gregor Piatigorsky died of lung cancer at his home in Los Angeles, California, in 1976. He was interred in the Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery in Los Angeles. Appraisal It has been reported that the great violin pedagogue Ivan Galamian once described Piatigorsky as the greatest string player of all time. He was an extraordinarily dramatic player. His orientation as a performer was to convey the maximum expression embodied in a piece. He brought a great authenticity to his understanding of this expression. He was able to communicate this authenticity because he had had extensive personal and professional contact with many of the great composers of the day. Many of those composers wrote pieces for him, including Sergei Prokofiev(Cello Concerto), Paul Hindemith (Cello Concerto), Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco (Cello Concerto), William Walton (Cello Concerto), Vernon Duke (Cello Concerto), and Igor Stravinsky(Piatigorsky and Stravinsky collaborated on the arrangement of Stravinsky's "Suite Italienne", which was extracted from Pulcinella, for cello and piano; Stravinsky demonstrated an extraordinary method of calculating fifty-fifty royalties). At a rehearsal of Richard Strauss's Don Quixote, which Piatigorsky performed with the composer conducting, after the dramatic slow variation in D minor, Strauss announced to the orchestra, "Now I've heard my Don Quixote as I imagined him." Piatigorsky had a magnificent sound characterized by a distinctive fast and intense vibrato and he was able to execute with consummate articulation all manner of extremely difficult bowings, including a downbow staccato that other string players could not help but be in awe of. He often attributed his penchant for drama to his student days when he accepted an engagement playing during the intermissions in recitals by the great Russian basso, Feodor Chaliapin. Chaliapin, when portraying his dramatic roles, such as the title role in Boris Godunov would not only sing, but declaim, almost shouting. On encountering him one day, the young Piatigorsky told him, "You talk too much and don't sing enough." Chaliapin responded, "You sing too much and don't talk enough." Piatigorsky thought about this and from that point on, tried to incorporate the kind of drama and expression he heard in Chaliapin's singing into his own artistic expression. He owned two Stradivarius cellos, the "Batta" and the "Baudiot." ****** Now, in the 21st century, the great Russian patriarch of cellists is Mstislav Rostropovich. However, 25 years ago, it was Piatigorsky who held that honored position. Piatigorsky was born in Ekaterinoslav (Dnetropetrovosk) Russia on April 17, 1903. He studied violin and piano as a young child with his father, until he saw and heard the cello at an orchestra concert, and became determined to be a cellist. He constructed a "play cello" of two sticks, a long stick for the cello, and a short stick for the bow, and enjoyed pretending to perform. When he was seven years old he was finally given a real cello, and began his remarkable life as a cellist. A student of Klengel told him he had no talent whatsoever, and to stay clear of the cello. Piatigorsky ignored the unwanted advice, and won a scholarship to the Moscow Conservatory, where he studied with Gubariov, von Glehn (who had studied with Davidov) and Brandoukov. While studying at the conservatory he earned money for his family by playing in local cafes. The October Russian Revolution occured with he was only 13 years old, and he began playing in a string quartet shortly thereafter, appropriately named the "Lenin Quartet." At the age of 15 he was engaged to be the principal cellist of the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow. Despite his success as a cellist, or maybe because of it, the Russian authorities would not allow him to travel abroad to further his studies, or to perform. He therefore defected into Poland by taking a cattle train to the frontier, and then fleeing across the border with his cello. Unfortunately his cello didn't make the crossing intact. Border guards were shooting at him and his companions, one of which happend to be a large lady opera singer. When the shots rang out, she grabbed Piatigorsky, crushing his cello. Neither Piatigorsky or the soprano were injured, as he helped her across the border. Piatigorsky, now 18 years old, traveled from Poland to Germany, and studied for a short time in Berlin and in Leipzig with Becker and Klengel, neither of which were much appreciated by him. He found employment playing in a trio in a Russian cafe in Berlin, frequented by the likes of Feuermann and Furtwangler, who heard him play and hired him as principal cellist of the Berlin Philharmonic. He kept that post until 1929 (now 26 years old), when he decided to persue a career as a traveling concert artist. When Richard Strauss heard him perform Don Quixote with the Berlin Philharmonic, he said, "I have finally heard my Don Quixote as I thought him to be." That same year he made his debuts with the Philadelphia Orchestra under Stowkowski, and the New York Philharmonic, with Mengelberg. (He loved the United States, and became a citizen in 1942.) He formed a chamber group with pianist Artur Rubinstein, violist William Primrose and violinist Jascha Heifetz. The group became very famous and recorded at least 30 long playing records. Privately he enjoyed playing chamber music with Horowitz and Milstein. Both the concert going crowds, and composers loved him, and many works were written especially for him, even as we now see in the case of Rostropovich. Both Piatigorsky and Rostropovich have a relationship with Prokofiev's Symphony Concerto Opus 125. Prokofiev had written a Ballade in 1938, for Piatigorsky, which he premiered with the Boston Symphony under the baton of Koussevitsky. Prokofiev later reworked his material into the Symphony Concerto, which he dedicated to Rostropovich. Piatigorsky collaborated with Stravinsky on a transcription of the Pulchinella Suite, which became known as the "Suite Italienne" for cello and piano. He became an influential teacher. From 1941 to 1949 Piatigorsky was head of the cello department at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, and taught chamber music at Tanglewood. The years 1957 to 1962 saw Piatigorsky heading up the cello department at Boston University, and then in 1962 continuing his teaching at the University of Southern California, where he remained until his death in 1976. In 1962 and also in 1966 he was a member of the jury of the International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow. It was also in 1962 that the Cello Society of New York honored him by beginning the "Piatigorsky Prize," awarded every other year to a deserving young artist. Piatigorsky owned two Stradivarius cellos: the "Batta" dated 1714, and the "Baudiot" dated 1725. He died August 6, 1976 from cancer, and was buried in Brentwood Cemetary, near Los Angeles. ***** One of the pre-eminent string players of the 20th century, Gregor Piatigorsky was born in Ukraine in 1903, and died in Los Angeles in 1976. His international solo career lasted over 40 years, and especially during the 1940's and early 1950's he was the world's premier touring cello virtuoso -- Casals was in retirement, Feuermann had died, and the three artists who were to succeed Piatigorsky (Starker, Rose, and Rostropovich) were still in their formative stages. His one true peer, Fournier, was limited in his travelling abilities by polio. Thus, Piatigorsky had the limelight almost to himself. He was gregarious, loved to travel and perform anywhere, and he hobnobbed as easily with farmers in small towns as he did with Toscanini, Stravinsky, Rubenstein, and Schoenberg. It was a legendary career. Piatigorsky was not a "child prodigy," perhaps, but his talent manifested itself early and carried him quickly upward. He began to play at age 7, and was accepted as a student at the Moscow Conservatory two years later. By age 15 he was principal cellist of the Bolshoi Opera. Escaping the upheaval of the Russian Revolution in 1921, he studied with Julius Klengel (also Feuermann's teacher) in Leipzig, and at age 21 became principal cellist of the Berlin Philharmonic under Furtwängler. In 1929 he left the orchestra to pursue a solo career. His first marriage (to Lyda Antik) ended in divorce (she later married Fournier!). He then married Jacqueline Rothschild and moved to America in 1939, becoming a US citizen three years later. He lived first on some property he had bought in the Adirondacks (and helped found the Meadowmount School with Ivan Galamian), then moved to Philadelphia (where he succeeded Feuermann as cello professor at Curtis), and finally settled in Los Angeles in 1950, where he taught with Heifetz at USC. He was a dedicated teacher, and the quality of his studio was legendary. His pupils included Lorne Munroe, Mischa Maisky, Nathaniel Rosen, Stephen Kates, Lawrence Lesser, Dennis Brott, John Martin, Christine Walewska, Rafael Wallfisch, Leslie Parnas, and countless others. There are too many highlights in his career to mention them all. His annual tours took him throughout the world, appearing with the greatest orchestras and conductors of the time. He made the first recording of the Shostakovich Sonata, collaborated with Stravinsky on his Suite Italienne, premiered the Hindemith Concerto of 1940 and Sonata of 1948, and commissioned or premiered many other works including the Walton Concerto in 1957. He was also a prolific arranger, and many of his transcriptions are published and performed the world over. Piatigorsky always loved chamber music, and was a member of three different piano trios - first with Artur Schnabel and Carl Flesch, next with Vladimir Horowitz and Nathan Milstein, and finally with Artur Rubenstein and Jascha Heifetz! Piatigorsky's recording career was fairly prolific, if somewhat spotty. His earliest recording, the Rococo Variations from 1925 on Parlaphone, already displays a well-formed sense of style and virtuosity, an "electric" sound that would become his hallmark. In the 1930's and 40's, he did most of his recording in London, for HMV or Columbia; in the 1950's and 60's he was an RCA artist. Among his finest solo recordings are an especially beautiful Don Quixote with Munch and the Boston Symphony, the Brahms E minor Sonata with Rubenstein, the Walton Concerto with Munch, the Debussy Sonata with Lukas Foss, and many of his short pieces from the HMV period. The specter of Casals kept him (and his classmate Feuermann) from recording any solo Bach, but otherwise his recordings covered all facets of the repertoire: Beethoven, Brahms, and Strauss sonatas, Dvorak, Saint-Saëns, Schumann, and Brahms Double concertos, encore pieces, etc. The bulk of his work for RCA consisted of chamber music recordings with Heifetz; they focused on works with piano or string repertoire other than quartets. Piatigorsky was a very tall man, well over six feet, and he handled his Stradivarius like a toy. He would stride briskly onstage through the orchestra, holding the instrument horizontally with one hand, like a lance. He often closed his eyes and turned his handsome face to his right as he played, giving a regal bearing to his performing profile. Due to his size, all the basic playing actions were simple for him; he had a huge sound, and drew full bows with same effort and extension that a smaller player like Casals needed for only half the bow. He could produce the widest spectrum of colors, from any spot on the bow. He delighted in quick changes of articulation, even if just for a few notes. Most dazzling of all was his staccato stroke, which is wonderfully showcased in a Kultur video entitled "Heifetz/Piatigorsky." There, in an arrangement he made of some Schubert Variations, he displays both a down- and up- bow staccato that is almost beyond belief, along with many other signature effects. His own set of variations on the famous 24th Caprice of Paganini is a minefield of specialized bowing challenges; no one has been able to play it with his ease and flair, though many have tried. His left hand too was a law unto itself; reaching 1-4 octaves in the lower positions was easy and natural for him, and he ambled nimbly and effortlessly around the fingerboard. Trills were, again, "electric," and he drew incomparable richness from the lower strings. However, not all listeners were taken with his vibrato. Given his size, he apparently had trouble controlling the full-arm motion that most cellists learn, and was more comfortable producing the vibrato from a wrist motion alone. This gave the sound a nasal quality at times. And, since he had to work less hard to produce the vibrato, he did not always attend to it with the care that someone with more ordinary gifts would, and some passages in his recordings grate on listeners brought up on the buttery sounds of Rose or Fournier. In his later years, this technique also began to effect his intonation. On balance, though, his playing displays a combination of stylishness, verve, and humanity that no one has ever matched. All of Piatigorsky's concerto and chamber music recordings for RCA are available on CD; there are at least two discs of recital works that have not been reissued, however. Most of the earlier material is also available on various historical labels such as Testament, Biddulph, Arlecchino, and Pearl. Interesting historical tidbits include the octave-jumping in the repetitive bridge passage leading into the 5th Rococo variation (1925); the inexplicable blending of pizzicato and arco triplets in the string accompaniment to the slow movement of the Schumann Concerto (1934); the added embellishments in the Chopin Polonaise, much different than the standard Feuermann version (1940); and another version of the passage that now consists of glissando harmonics in the second movement of the Shostakovich Sonata (1940). As mentioned, the Don Quixote with Munch is one of the greatest recordings ever of the work (which has had many great recordings, all of them on RCA for some reason), and the Kultur video belongs in every cellist's collection. There is a spectacular BBC film of the UK premiere of the Walton Concerto; God willing, someday they will see fit to make it available to the general public. For me, though, the quintessential Piatigorsky is heard on his live recordings and airchecks, despite sometimes poor reproduction. When onstage he seemed to draw energy and inspiration from his colleagues and from the audience; despite the occasional technical slip the music-making is always white-hot. There is, or used to be, a CD available of Schelomo with Rodzinsky and the NY Philharmonic from 1944. While Piatigorsky forces the sound sometimes, and ensemble is not perfect, it is a spellbinding portrait of a great performing artist at the peak of his powers, captured in full flight. Experiences like that heard on this recording are simply not to be had today; no one gives so much of himself anymore. Piatigorsky's legacy is deep and broad. Aside from the transcriptions that we all play, the annual seminar in his name at USC, where gifted young cellists from all over the world come to learn from top solo professionals, and the wonderful recordings and films, above all there is the legacy of spirit. Every Piatigorsky pupil I've ever spoken to had only the warmest praise for the man, his teaching, and his devotion to the fullest development of each student. His artistic vision has been passed down through younger artists, and thence to their pupils throughout the world. He has left the music world incomparably richer for having passed through it, and all of us are beneficiaries of his life. ebay2828