-40%

1950 Original PHOTO Jewish VIOLINIST Violin MIRIAM SOLOVIEFF Judaica HOLOCAUST

$ 39.6

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

DESCRIPTION:

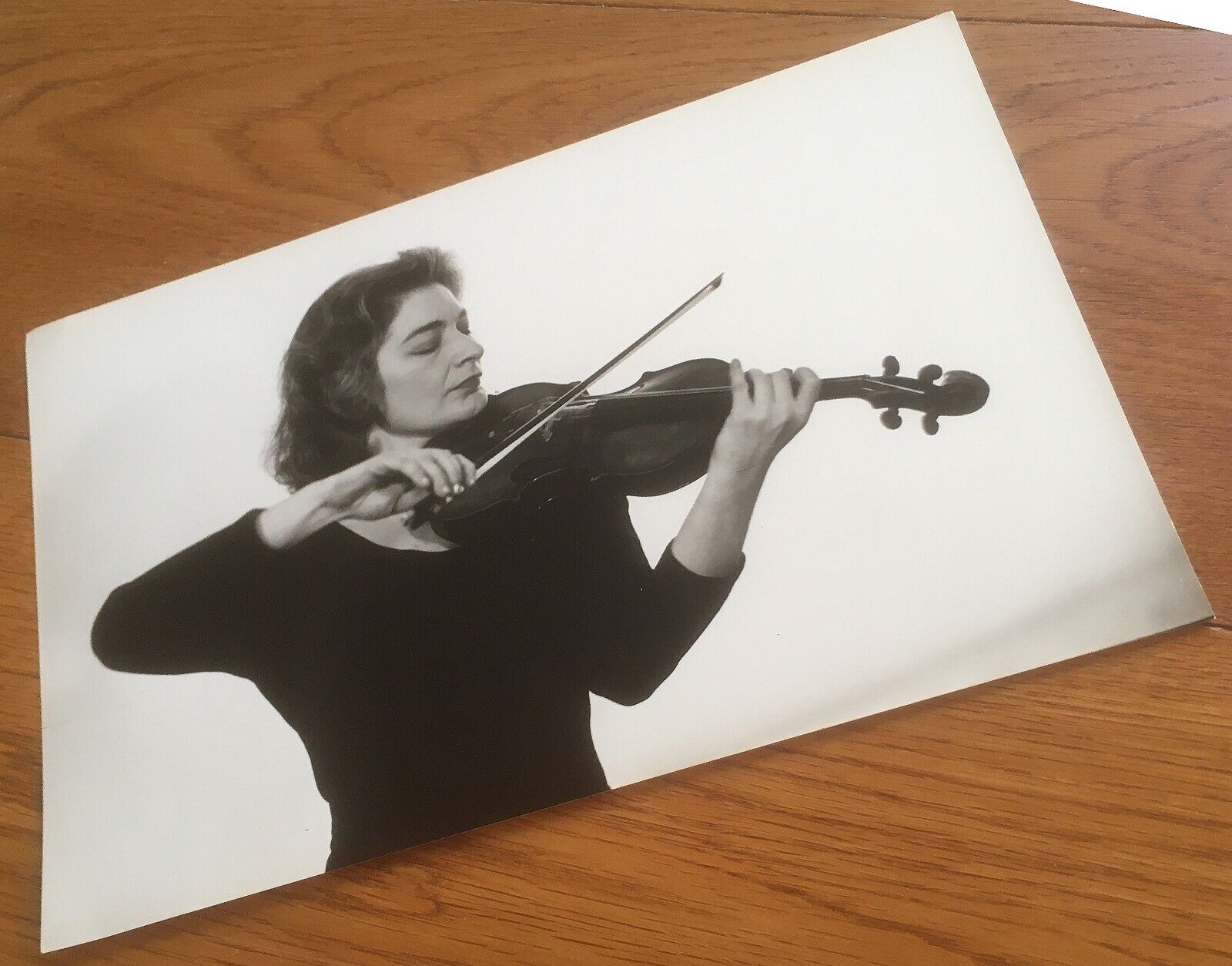

Up for auction is an ORIGINAL ACTION PHOTO of the

renowned beloved JEWISH American VIOLINIST and VIOLIN TEACHER of Russian descent - MIRIAM SOLOVIEFF

.

During the Second World War she worked as a violinist for the US Army's troop support and also gave concerts in the liberated concentration camps of Buchenwald and Auschwitz.

The PHOTO is an ORIGINAL REAL ART PHOTO

( Silver gelatine ) depicting YOUNG and HANDSOME MIRIAM emotionaly playing her VIOLIN at the age of 30-40.

The size of ORIGINAL REAL PHOTO is a

round 10

x 7 " .

Very good condition

( Pls look at scan for accurate AS IS

images ) Authenticity guaranteed. Will be sent inside a protective rigid packaging .

PAYMENTS

: Payment method accepted : Paypal .

SHIPPMENT

:SHIPP worldwide via registered airmail is $ 19 . Will be sent inside a protective packaging

.

Handling around 5-10 days after payment.

Miriam Solovieff (also: Myriam Solovieff ; born November 4, 1921 in San Francisco ; † October 3, 2004 in Paris ) was an American violinist and music teacher. The daughter of an orthodox Jewish emigrant from Russia had piano lessons from the age of three. From 1928 she also had violin lessons with Robert Pollack at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music . After he went to Japan, she was tutored first by Kathleen Parlow's assistant , Carol Weston , and then by Kathleen Parlow herself. After performances for the Pacific Musical Society and the Community Playhouse , among others , she made her debut in 1932 in the Young People's Symphony Concerts with the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra conducted by Basil Cameron and was then invited by Artur Rodziński to give a regular concert with the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra . From 1933 to 1937 she studied with Louis Persinger , teacher of Yehudi Menuhin and Ruggiero Ricci . In 1934 she performed with the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra at the Hollywood Bowl in front of an audience of 1,000under Ossip Gabrilowitsch with Mendelssohn 's Violin Concerto, in 1937 she made her debut in the Town Hall of New York. In 1938 she traveled to Europe to study with Carl Flesch and gave concerts in Belgium, the Netherlands and England. In 1939 Solovieff was an eyewitness when her father shot her mother, her sister and finally himself because of marital problems; she herself escaped unharmed. During the Second World War she worked as a violinist for the US Army's troop support and also gave concerts in the liberated concentration camps of Buchenwald and Auschwitz. In 1946 she gave a concert with the Wiener Symphoniker conducted by Jonathan Sternberg . In the 1950s Solovieff settled in Paris as a violin teacher. In the mid-1960s she recorded the complete Brahms violin sonatas with Julius Katchen , but the recordings were never released commercially. ***** Another rather neglected violinist is Miriam Solovieff (1921-2004). As our first CD release will be soon out of stock, we have decided to release a second CD. She only left few commercial recordings according to James Creighton's "Discopaedia of the violin" and none of the presented repertoire on our CD has been previously released by Miriam Solovieff. December 28, 1939 was the most tragic day in Solovieff's life as she dodged two bullets and escaped injury when her father, shot and wounded her mother Elisabeth (38) and sister Vivienne (12) and killed himself in their fashionable Riverside drive apartment in New York. Her father (41), who had been estranged from his wife for 5 years died a few minutes after the shooting. Her mother was wounded in the abdomen and was expected to die and her sister was struck in the neck and had an even chance to survive. Her mother and sister died of the wounds the day after. Vivienne, was already being praised as a precociously competent pianist when she was 4. Left as the only surviving member of a family, Miriam’s life was forever marked by this tragedy and it was a vain effort to continue her career. פחות *** Johann Sebastian BACH (1685-1750) Partita for Violin Solo No.2 in D minor, BWV 1004: Chaconne (ca.1720) [15:39] Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART (1756-1791) Sonata IV in E minor, K304 (1778) [12:09] Johannes BRAHMS (1833-1897) Violin Sonata No. 3 in D minor, Op. 108 (1888) [21:07] Miriam Solovieff (violin) Julius Katchen (piano) rec. 13 January 1963, Paris, Studio 107, Le Livre d’Or, Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française MELOCLASSIC MC2007 [49:06] Miriam (or Myriam) Solovieff (1921-2004) had an extraordinary life. She was born in San Francisco and began to study the piano but after the epiphany of hearing the ten-year old wunderkind Ruggiero Ricci in 1928, she asked to be able to learn the violin. She was a pupil of Robert Pollak, then Carol Weston – who was the teaching assistant of the leading Canadian fiddler, Kathleen Parlow - and then, for four years, Parlow herself. Her first appearance with orchestra came in 1932 when she performed two movements of Lalo’s Symphonie espagnole with the San Francisco Symphony conducted by Basil Cameron. Artur Rodzinski duly invited her to Los Angeles. Further studies followed with Louis Persinger, the teacher of Ricci and Menuhin, and then a year in Belgium with Carl Flesch. She returned home to America, to the family apartment, now in New York, in November 1939. A few weeks later, between Christmas and New Year, her father, estranged from her mother, shot and killed his wife and Miriam’s twelve-year old sister Vivienne and then killed himself. He had begun the spree by shooting at Miriam but had missed. The war curtailed her career but she married and resumed playing and touring in late 1945, playing across Europe, including visits to concentration camps to play there. She moved to Paris in the 1950s, taught, performed, but had a breakdown in the early 1960s. Thereafter her performing career seems to have trailed off although she did teach. She died in Paris in 2004. The story is thus one of initial brilliance, a charmed childhood prodigy in the mould of Guila Bustabo or of Ricci, her fellow San Franciscan, followed by years of study with two of the world’s great teachers – Persinger and Flesch. Thereafter came family tragedy and the disruption of the War, followed by exposure to European horrors, and a traumatic breakdown. Solovieff made few commercial recordings. So far as I’m aware she did make one 78, with sweetmeats by Chaminade, Kreisler and Debussy, on the Cupol label. In Vienna she taped the Lalo Concerto in F with Swoboda, with whom she also recorded Schubert’s Rondo. The one LP that does crop up fairly often is Scheherazade, made once again in Vienna with Rossi conducting. She recorded the three Brahms sonatas with Julius Katchen in the early 1960s but it was at these sessions that she suffered her breakdown. There is some conflicting information about this. Both Meloclassic’s notes and Eric Shumsky – who studied with her and admired her greatly – suggest that these recordings were never issued. They may, however, have been assigned a catalogue number as I’ve seen Decca SXL6209 mentioned in relation to these Solovieff-Katchen recordings. Ironically, whilst Katchen’s recording of the three sonatas with Josef Suk is very well known, he also recorded Nos. 2 and 3 with Solovieff’s one-time violinistic spur, Ruggiero Ricci, again for Decca. Which, at last, brings us to this 1963 Paris studio broadcast. She plays the Bach Chaconne in a measured, precise, stylish way, very different from, but at a similar tempo to, Oscar Shumsky’s later performance. It, therefore, stands at a remove from the Franco-Belgian approach propagated by Grumiaux or Enescu who took a far more tensile approach. The playing here is characterised by dignity and control, not by overmuch drama in the contrastive passages. Rubati are languid at points. It was a work she had played often – she had played it pre-war at the Wigmore Hall in London, where critics felt her technical gifts ahead of her interpretative ones. The two-movement E minor Sonata of Mozart, K304 reveals a deft ensemble with Katchen. She evinces good tone colours and a well-equalized scale and plays with musicality and style. The D minor Brahms Sonata alerts the listener as to what these two musicians did with their Brahms. I should note that their studio cycle of the three sonatas, alluded to above, whether issued commercially or not does still exist. Perhaps it is time for it to be definitively released. The playing of Op.108 is sensitive and without expressive exaggeration. It is not nearly as personalised as the Ricci recording with Katchen but is on a par with the Suk, though she lacks his range of tone colours. She essays one or two quite eager portamenti and can float her tone with sufficient body. There is no lack of rapport here. The interpretative approach is pretty consistent with the Suk-Katchen. This 50-minute recital will be particularly intriguing to violin collectors, for whom Solovieff may be no more than a name, if that. The broadcast sound is excellent. Jonathan Woolf ***** ARTS & CULTURE Miriam Solovieff—A Great Violinist and Superb Teacher BY ERIC SHUMSKY TIMEAPRIL 13, 2010 PRINT A very old and treasured photograph of violin great Miriam Solovieff (Courtesy of Eric Shumsky) A very old and treasured photograph of violin great Miriam Solovieff (Courtesy of Eric Shumsky) To have received the feeling that all is possible and within grasp is surely necessary for an artist. Miriam Solovieff, the great violinist, gave me that feeling when she taught me. She had a great heart and really cared. Without a doubt she was one of my best teachers—just as I imagine a great Olympic skating coach might be. Miriam Solovieff (d. 2004) was born in San Francisco in the early 1920s and was a family friend of my father Oscar Shumsky, as well as my Uncle William Carboni. But I learned little of her life in those years. Later I discovered that Solovieff’s role model was actually not a violinist. In fact, it was Maria Callas whom she really loved. She actually looked like Callas in her younger years. It was the beauty of the character portrayal being at one with the music that Callas epitomized for her. Naturally Solovieff’s flare for the dramatic was obvious, but really it was not a question of the dramatic. It was a question of making a character stand out, since to be a little speck on a tree did not interest her. I studied with her in Paris in the 1980s, and this was the time that I got to know her. Although she no longer played at the time, her recordings of the Brahms "Sonatas" with Julius Katchen (sadly, never released), and the Schubert “Rondo,” as well as Rimsky Korsakov’s “Scherazade” can be found, and they reveal her wonderful talent. My lessons would last for three hours, and then I would take her out for a lovely dinner, and we would talk for several more hours over good wine and beautiful French cuisine. She had a very strong personality, and one needed to be on guard so as not to make a superficial comment which she might take the wrong way. Miriam Solovieff had a reputation in Paris for saying something like: “You have no business entering this contest," or “You really should not be playing that piece.” I heard the reports, and I knew the people who voiced these complaints. Yet if these musicians had been honest with themselves and stepped up to the plate with an earnestness to resolve the issue, she might have responded differently. If she respected your earnestness, she was there for you. She was a superb teacher. Hers was not an abstract approach at all. In fact, she was very straightforward—just play as beautifully as possible. This was no easy task. When I played badly, she really let me have it with nothing held back. The rough bow change or the false accent—she mimicked them back to me, and hearing the sound myself felt like a Mike Tyson punch to the face. I came to realize that an accent in the wrong place destroyed an otherwise lyrical passage. She never swept intonation problems under the rug. When she came to my concerts, sometimes I could tell by the look on her face what she thought, and then I did not ask for her opinion—I actually already knew. At other times when I really played well, she made me feel that my playing was on the highest level and ranked among the finest. She could be brutally honest, but, in my case, she was actually hugely supportive. She even pointed out to me that I seldom supported myself even when things went well. Where some teachers would make a neurotic problem out of a fault, she would present a simple solution which would always improve the way something sounded. One last note: When Solovieff was still a child prodigy, her father murdered all of her family in front of her eyes and tried to kill her as well. She narrowly escaped, and then her father took his own life. Her mother, on her deathbed, pleaded with Miriam to play her Town Hall debut a few days later in New York City. Miriam followed her mother's wishes and played a gorgeous recital, attended by many prominent figures. This feat in itself testifies to the great talent and character of Miriam Solovieff. Eric Shumsky is a concert violist. ebay5917 folder 206